Hi everyone. I’ve been away for a while due to a personal bereavement which I’m still dealing with, however I’ve got myself together enough to get back to writing. In fact this was one I wrote before that happened, I just needed to do some final edits. There is more to come from me very soon.

I've been using AI to help me unblock my creativity, as I said here, but I'm still in two minds as to whether it's a good idea or not.

I've used Claude, o3 mini and Gemini Flash, among others, to help me complete a load of unfinished drafts, which is a load off my back, and means that people who subscribe to this newsletter will actually get to read things that would otherwise have stayed unfinished forever.

But... when I use an LLM to help flesh out an idea, polish a paragraph, or even to generate a first draft based on my notes, there's a voice that whispers: "This is cheating." It doesn't matter that I still provide the seed ideas, that I edit heavily, that the final piece still requires my judgement and discernment. Something about the ease of it all feels wrong.

The Spectrum of AI Collaboration

I'm coming to realise that it isn't a simple yes/no determination about using AI, but rather a spectrum of involvement:

At one end, there's using AI simply to check grammar or suggest alternative phrasings – something not fundamentally different from using a thesaurus or spell-checker. At the other end, there's asking an AI to generate entire works with minimal human input. And of course we will see entire books generated out of someone's idle shower thoughts, or whatever is trending on Google,... as if we need more bullshit in the world.

But most of us working with these tools fall somewhere in between. I might have the structural ideas and main points of an essay, but use AI to help flesh them out. Then I'll rewrite certain sections, add my own commentary, and shape the final piece. In these cases, the AI might generate 70% of the initial words, but the vision, direction, and final decisions are mine. So in that sense, I'm like a film director, and the AI is my actors and crew.

The Value of Struggle

There's something deeply ingrained in humans that connects value with effort. When we struggle to create something – imagine a tortured artist wrestling with words late into the night, filling wastepaper baskets with rejected drafts – that struggle becomes part of the narrative we tell ourselves about the work's worth.

We romanticise the suffering artist for a reason. There's that Hemingway quote about writing: "There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed." We've built an entire mythology around creative suffering.

This isn't merely cultural romanticism. Psychologically, we tend to value more deeply what we've invested ourselves in fully. Researchers call this the "IKEA effect" – we attach greater value to things we've put effort into creating, even if the objective quality isn't higher. It certainly isn't when the person putting together the coffee table is me.

Maybe, way back in the day, those who were able to light fires were highly respected. Then we got matches, lighters, and so on, and the respect afforded to elite pyromaniacs moved elsewhere. Is writing any different? We can hardly argue it's more important than keeping warm or cooking our food.

So maybe creative struggle isn't disappearing so much as shifting. The effort now lies more in curation: in conceptual clarity, in discernment, in the integration of machine outputs with human perspective. These forms of creative labour may not feel as visceral as the traditional wrestle with the blank page, but they represent genuine engagement with the creative process. Maybe the struggle was overrated anyway. Yet there is something there.

The Question of Aura

Walter Benjamin's concept of "aura" offers another perspective on this dilemma. In his 1935 essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," Benjamin explored how technologies like photography transformed our relationship with art.

For Benjamin, the "aura" represented the unique presence of an artwork – its authenticity, its embodiment of the artist's touch and labour, its historical journey. He argued that mechanical reproduction diminished this aura. When art could be perfectly copied, something of its uniqueness was lost. It's true that a printed book has lost something compared to a hand-illuminated manuscript. But we can hardly argue that the printing press has been a net negative, can we?

AI collaboration raises even more profound questions about aura than mechanical reproduction did. What creates the "aura" in an AI-assisted work? Perhaps it's the uniquely human elements – the initial vision, the discernment in selection and editing, the personal significance of the themes explored. Also the slight errors, the typos, the surprising choice of word. The Sufis say 'only God is perfect'... well maybe only God, and Large Language Models. Yet there is something more to 'perfection' than a mere lack of error.

Perhaps the aura now resides more in the story of creation – the particular conversation between human and machine – rather than solely in the final artefact. Each human-AI collaboration has its own unique character and development.

Learning Through Co-creation

My friend

observed in the comments to part one of this exploration that working closely with AI "has made me a better writer: I've been training how to question each word choice, each sentence I generate." She also notes the importance of maintaining one's confidence as a writer and not becoming enslaved by the tool.I've found something similar. By creating a system prompt that includes examples of my own writing, I've been able to see my own style reflected back to me in the LLM's outputs – and not always flatteringly. It's like looking in a mirror and seeing one's flaws, even if the reflection is a slight caricature. I could see that my style has been too ponderous, too eager to cover every eventuality.

As a counterbalance, I created another prompt for a "brutal critic and editor" that points out unnecessary verbiage. The back-and-forth with this AI editor has been illuminating, not unlike how Carlos Santana described his approach to guitar practice: constantly throwing away the clichés that have crept into his playing.

Finding Balance

Carlota shared her personal rules for working with AI: "Everything you write that you actually care about – books, essays, emails – should come from you and you only. You're allowed to use the AI only 1) when you don't know a particular term; 2) when I'm done writing, re-writing, editing and re-editing and I can't make the piece any better out of my own brain."

I find this to be a solid approach. It preserves the core creative act while acknowledging the utility of these tools in specific contexts.

I'm still figuring out where my own boundaries lie. I know I don't want AI to write my essays for me – "it's not me: it's similar but not as good," as I said to Carlota. But I'm also open to the ways these tools can enhance rather than diminish my writing.

A Renaissance of Discernment

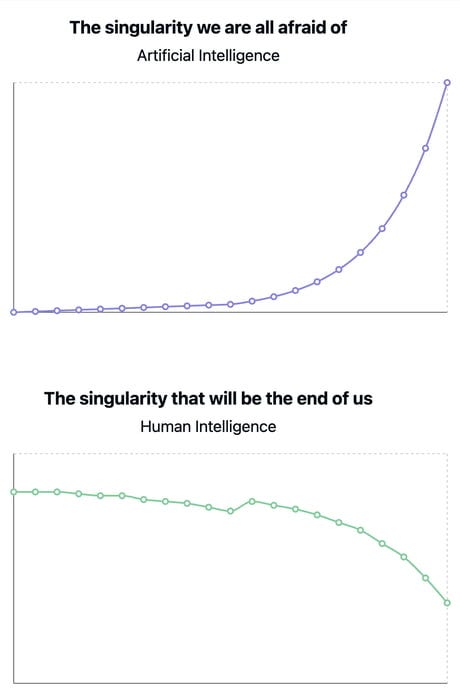

As we move into a symbiosis with machine consciousness, I believe what will become increasingly valuable is what I've called the "Renaissance of Discernment" – our ability to hone our sense of poetry, of intuition, our 'right brain' capabilities.

These are the aspects that AI doesn't have. They're what allow us to immediately spot who is churning out "AI slop" and poisoning the intellectual commons, versus who is creating more clarity (even if they use AI tools to help them).

The invention of the camera didn't eliminate painting, though it certainly altered it. In the same way, I don't think LLMs will completely take over writing. Instead, they'll push us to focus on the aspects of creation where human consciousness adds the most distinctive flavour and value.

The key word is probably 'value', which comes from aura. If the ideas are deeply felt and have been marinated in the human mind sufficiently, I don't think it's that important if AI has been used as a midwife to get them out into the world. Curation is also a skill. A great DJ can inspire as much as a musician, and we are going to need curators more than ever to help us navigate through the river of slop now coming our way.

I may change my mind about this. I might even become anti-AI. To me, having some cognitive flexibility is always better than being a zealot, as much as the algorithms try to make everything as polarised as possible. I think ultimately cultivating that sort of critical yet flexible attitude, which is part of discernment, is the key to enriching, rather than poisoning, our intellectual commons.

cover photo is by Christina @ wocintechchat.com on Unsplash

I loved this post and resonate with everything you say.

Good to see you're back, and I was sorry to hear about your loss. Thanks for the post. Very thought-provoking.